Credit: rawpixel.com

Our forefathers may be long dead, but they still shape the places we live and the lives we lead.

Cityscapes, commerce, laws, wars – their legacy defines us in so many ways.

Their names are cut into the stones in our squares and their statues watch over our parks and public spaces.

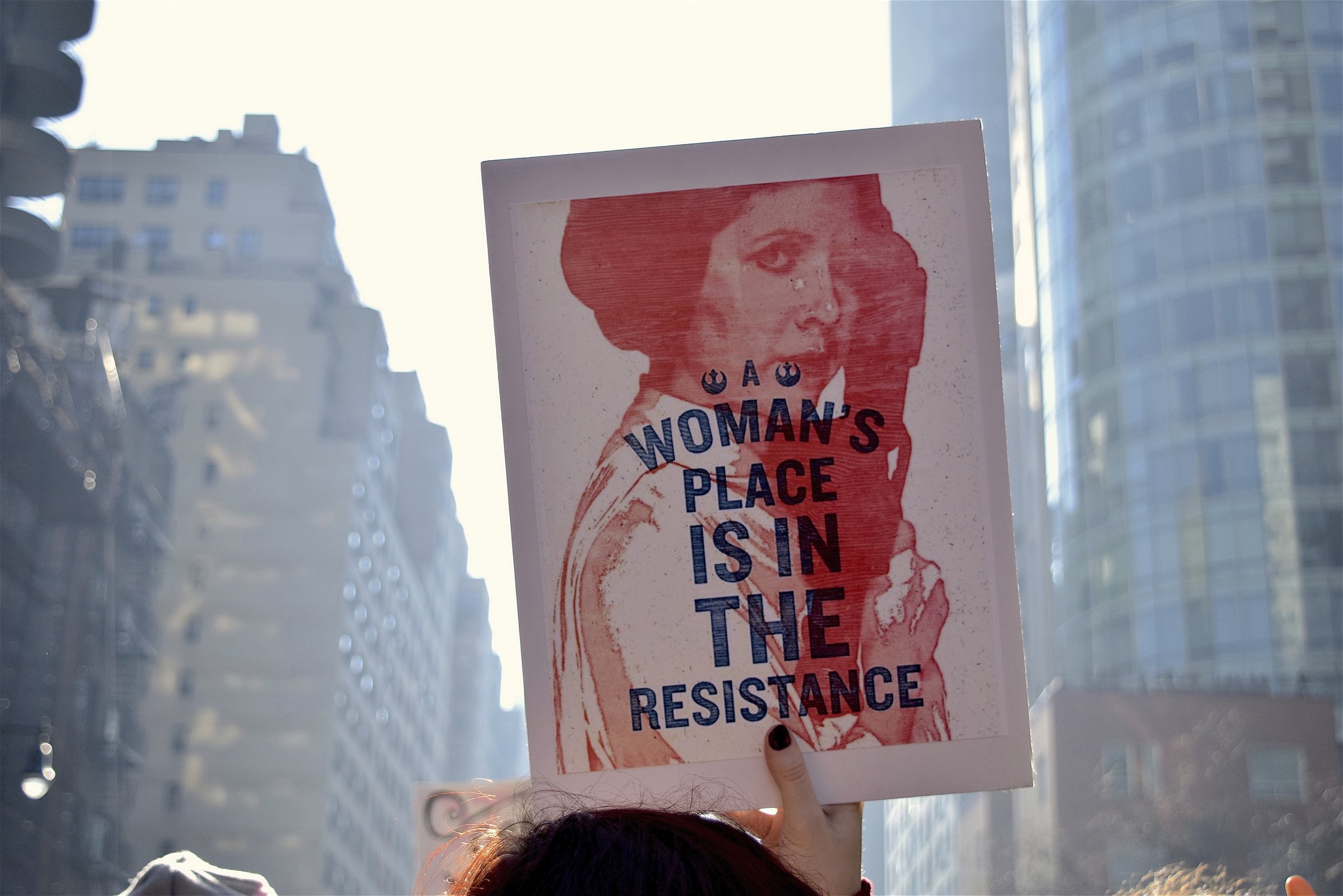

But what about our foremothers?

Even the word sounds strange. Google ‘forefathers’ and twenty million results appear in a split second; try ‘foremothers’ and the total’s less than 300,000.

So many of the women who came before us are shadows, their memory like vapour.

Yes, there’s a (contested) movement to get more women on our bank notes, to squeeze in a statue here or there.

But there’s also a whole lot of silence.

The thing is, it’s hard to know who we are and where we’re headed if we don’t know who and where we’ve come from.

Sometimes, though, like the ruins that appear when waters recede in a drought, something unexpected breaks the surface.

That happened recently, when a foremother who once lived where I do caught my attention.

After a sunny summer wander on Wimbledon Common last year, I noticed a name on a plaque that called to mind a college I knew from my daughter’s time at university. A wave of nosiness took me to Wikipedia – and the discovery of my new favourite person.

She was dynamite – a genteel nineteenth-century woman who ruptured the social strictures of the time that kept middle-class women preoccupied and left working-class women exposed to unspeakable risk.

After her death, Cambridge professor James Stuart said, ‘…she was among that few great people who have moulded the course of things.

The world is different because she lived.’

And hardly anyone I ask knows anything about her.

Josephine Butler was born in Northumberland in 1828, into a family inspired by a close reading of the Christian gospels to take an active interest in political affairs and social reform.

She moved to Oxford in 1852 after marrying academic and priest George Butler.

It wasn’t a welcoming place for a young woman with an independent spirit and a lively brain. Women were excluded from academic life and study – and wouldn’t receive the university degrees they’d eventually earn for a further seven decades.

Instead, a woman of Butler’s background was expected to invest her energy in running a refined and decorous home.

I first lost my heart to Butler when I read what she did with hers – a gracious house on Oxford’s High Street.

She made it her business to get to know local women who’d been prostituted and sexually exploited, then opened her doors and invited them to come and make her home their own.

She and George learned of the case of a very young girl left pregnant and abandoned by a university don. His career continued undimmed. The girl, in desperation, killed her newborn and ended up in Newgate Prison.

The Butlers invited her to live with them on release – in recognition of the wrongs done to her as well as by her, and to save her from destitution.

During her time in Oxford, Butler frequently found herself the only woman at social gatherings. What she heard often frustrated her, but her response was a resolve ‘to speak little with men, but much with God.’

She more than found her voice, however, after moving to Bristol, Cheltenham and then Liverpool.

Her actions went on to change the warp and weft of our society, closing gaps and broadening freedoms we still enjoy.

But it was costly, and came out of profound personal pain.

In 1864, her 5-year-old daughter Eva died in an accident at home, and Butler later wrote that she ‘became possessed with an irresistible urge to go forth and find some pain keener than my own’.

In Bittersweet, author Susan Cain explores the idea that our most significant contribution may come out of our greatest loss.

Eva’s death seems to have lit a fuse in Butler. An unwavering belief in the value of each human life had long fuelled her generosity towards working-class women and girls, and intolerance for the attitudes that demonised them. Now she got to work.

The Contagious Diseases Act was designed to ensure a disease-free supply of women for exploitation, particularly by members of the British Army and Royal Navy. Any woman or girl considered to be a prostitute (no evidence was needed) was legally bound to undergo a physical examination – described by Butler as ‘surgical rape’ – and be confined to a ‘lock hospital’ if found to have a sexually transmitted disease.

She spent years organising, campaigning and speaking out against it, crisscrossing the country and then the continent.

She took on new challenges – tackling the trafficking of British women to Europe and an age of consent set at 13. Her long, nation-changing journey took her from prisons and provincial meeting halls to Parliament, through setback after frustrating setback.

But her sights were set and nothing was going to knock her off course.

In the end, her decades-long fight got the Contagious Diseases Act repealed and child prostitution outlawed.

(You can read more here and here.)

Learning about her life has had a powerful effect on me (and the friends and family who’ve had no choice but to hear all about her over the last year).

It’s made me wonder what ‘good trouble’ she’d be getting into today.

And reminded me that strong words, generous acts and unshakable commitment can change systems and structures that seem unassailable.

That feels like something worth remembering at the moment.

SDG